2024 Books

I didn't read a huge amount of books last year but I felt the quality was very high overall, with decent variety, too. Here's hoping 2025 is even better.

The Art and Science of Teaching Primary Reading by Christopher Such

This was fantastically useful and also rather disappointing. Useful because it is a great review of current research on teaching methods for reading, complete with suggestions for structuring lessons. Terrifying because I came across some critical elements of reading instruction that I haven't been covering sufficiently - for years. "Oops is the sound we make when we improve our beliefs and strategies."

This book should really help improve my teaching practice and I expect to have more to say about Such's work going forward. He has a follow-up coming out this year.

Learning in Depth by Kieran Egan

I enrolled in a 6-week intensive Learning in Depth summer course. Now I am mentoring a 30-week version and I have launched an experimental program at school using similar techniques. Needless to say there's something important here. Egan's ideas have changed the way I look at teaching. That said, much of the book contained things I'd already experienced firsthand when actually taking and teaching the courses. Later contributors have added a lot to my conception of LiD.

The appendix was one the best succinct descriptions of his major theories and how Egan thinks his paradigms fit into his critiques of existing educational ideas.

Children of Dune by Frank Herbert

He continues his rumination on the limits of power. Foreknowledge as a trap. The limitations of leadership and governance, the Fremen Mirage. It's all there. This time with more of a plot. I think that by this point Herbert had ironed out the details of much of the the lore. If you are interested in seeing more of the inner workings of the Dune universe, things are laid out more clearly here than in any previous book.

God Emperor of Dune by Frank Herbert

One observation about Dune is that the characters and organizations operate with much more coordination and certainty than people in real life. For example, the Bene Gesserit or the Spacing Guild, or the Ixians or any of the noble houses sort of collapse into individual actors much of the time. Individual characters take decisions or draw conclusions based on very certain readings of others' motivations. For example, mentats conclude mechanically that certain things must be so when real-world reasoning would at best present a balance of probabilities.

This is a general feature of fictional worlds for the sake of helping the reader keep track of the story and to help transmit themes. In Dune, however, it works well because it heightens a certain surreality or perhaps hyperreality of the story. Many of the characters have a super-human self discipline and faculty of reasoning and function as stand-ins for various themes and ideas; symbolism blends with reality. I like that it adds to the flavor of his work, but this quality also makes some of Herbert's philosophical conclusions come off less convincingly than if his stories more closely modelled our banal, uncertain, normal world.

On further reading, there are plot reasons why essentialism seems heightened in this book particularly.

At the end I am still trying pinpoint ****'s exact aims and similarly distill Herbert's primary messages. I won't write any more here for fear of spoilers. Overall I enjoyed this a lot, (perhaps second only to the original?) and a good point for me to put down the series.

A brilliantly-written book about a fantastically turbulent time in Indian (and global) history. I read this on the suggestion of a board game instruction manual (John Company) and it was funny, informative and thoroughly engrossing. Dalrymple has an expert eye for anecdote and really brings the turbulent and often horrific period alive. The idea that early venture capitalists crossed with sea captains might find themselves in charge of the most powerful empire in the world is just fascinating. Spoiler: nobody planned it.

Also, the quotes are just fantastic: "By God, Mr. Chairman, I stand astonished by my own moderation." - Robert Clive, in Parliament at hearing describing the plunder of Murshidabad.

How the World Really Works by Vaclav Smil

This was my second book by Smil. It is not as comprehensive as Energy & Civilization, but it is shorter, less dense and provides more information about contemporary life.

The book's main thesis is modern material imperatives are not likely to change quickly. They are part of the infrastructure that makes the modern world work. Without radical changes (massive behavioral change or catastrophic death counts) we can't make big changes to civilization's underlying material and energy needs in a short amount of time. Comparing material, infrastructure and energy to digital and electronic revolutions is a category error: these latter changes are enabled by and contingent upon the former. A lot of prediction is simply fantasy. We are not likely to go extinct from climate change and yet we also cannot eliminate it completely. Limiting to 1.5C is a fantasy.

There are, however, big and actionable changes we can make. These are: switching coal for natural gas, extending use of renewables, including nuclear power, eliminating food waste and eating less meat. Limiting general consumption, especially in rich countries, and substituting local alternatives to distant imports. We can also better managing water usage, better managing land usage and overuse of fertilizer. Smil comes off pessimistic about technology but I do think he would advocate for certain types of further scientific research: for example genetic engineering of nitrogen-fixing grains would be amazingly powerful. He nods to many issues that are essentially cooperation problems though here he does not provide many solutions. The book was useful and informative, but it can come off a little cranky.

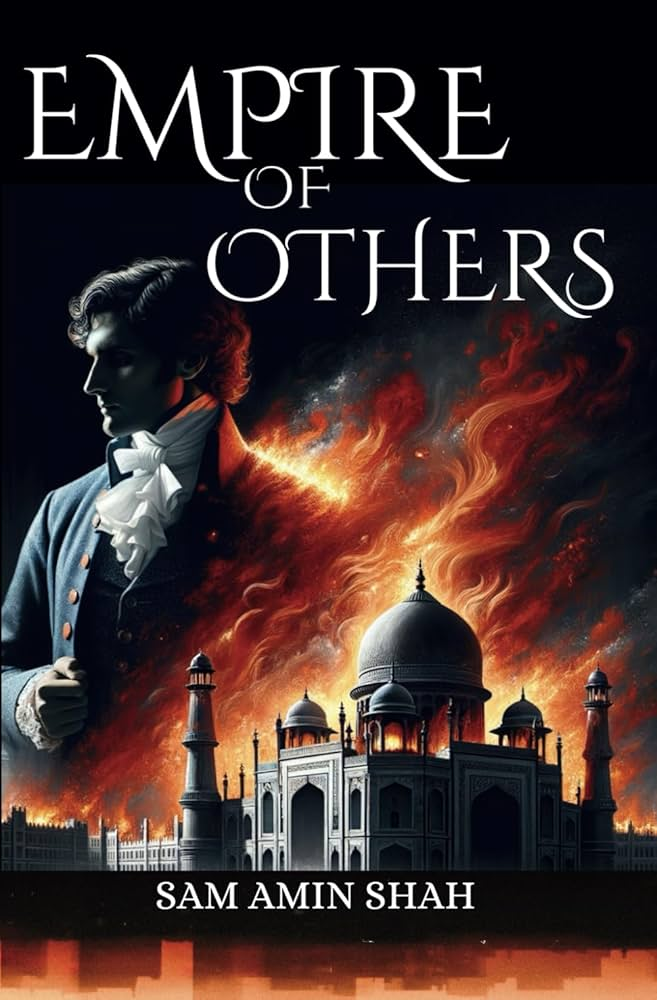

Empire of Others by Sam Amin Shah

This book was written in three months as part of a friendly bet between friends. I agreed to read and review it because I know the author and I must say I was very pleasantly surprised. Not that I thought it would be bad- but I did think it might be rushed. It was very compelling! The book is hard to categorize - part fantasy, part historical fiction, part 19th C. epic novel. It explores a fantastical version of the East India Company as it would have felt from the inside and slowly zooms out to see how this world of romance, intrigue and excess affects the 'Others' financing it. The question novel asks is how a moral person can conceive of duty from inside such a structure. But this isn't a moral slog! It's actually a cracking adventure stuffed with intrigue, conflict and revelations. I want more of this world.

Funny, too: "You are a low-born, garrulous henchman who pissed on my feet when he aimed for the moon."

The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin

Incredible. The writing itself can be rather plodding and the characterizations are flat. However, the ideas presented are so huge, beautiful and so far beyond what most books would even attempt that I can forgive any amount of prosaic delivery. I love that Liu Cixin wants to explain to you why the ideas are plausible, the beauty in the science. The fact that he doesn't assume you will suspend your disbelief over the science makes you willing to do so when it is necessary. A really lovely book. I enjoyed the Netflix adaptation as well.

The Dark Forest by Liu Cixin

Wow, this one takes the ball and runs. There were some wonderful upheavals of expectation. I'm going to take a break so that I can savor the next book. A few comments with spoilers at bottom of post: 1

Read this at the recommendation of a friend. It wasn't exactly my style but the premise held promise. Then some things happened in real life that made it more relevant. I don't regret reading it but it's hard to know who to recommend this one to.

Potential spoiler and explanation at bottom: 2

So You Want to Be a Game Master by Justin Alexander

The best book for a prospective game master out there, bar none. It walks you through creating a campaign and characters, designing and running different types of adventures, including location-based adventures, exploration and mysteries. There is advice on worldbuilding, tracking game information, running combat, playing NPCs and much more. The book is system-agnostic, and builds upon the information freely available on Justin Alexander's website but it is more useful because it is so well organized. I learned a lot from this and I have been playing and running RPGs for years. Highly recommended.

Dolmenwood Player's Book

Dolmenwood Monster Book

Dolmenwood Campaign Book by Gavin Norman

Dolmenwood is an immense, densely-packed, incredibly interlinked fantasy woodland hexcrawl with a fairytale flavor. The quality of the setting material is higher than almost any RPG I've ever seen. The amount of work that went into ensuring that the information is usable, easily referenced and clearly presented is, frankly, flabbergasting. The setting is bursting with detail, mystery, and billions of options but it feels so accessible that it begs to be played. I was planning to do a full review but I'm not sure if I'll ever get around to it, so this will suffice for now.

These books contain a complete RPG including rules, setting information and reference materials. I have run players through parts of the setting using Worlds Without Number rules because we started before the rules were finished, but the rule system seems perfectly serviceable (most similar to Norman's Old School Essentials). There is an vast amount of content and the bones of this setting could provide a sandbox for years of gameplay.

Touching the Art: A Guide to Enjoying Art at a Museum by Luc Travers

I read this after reading Brandon Hendrickson's blog post on appreciating visual art. The book is brilliant, short and effective. It outlines a way of make visual art appreciation a more participatory and emotionally engaging experience. Note that it hinges visual art that contains human figures. Perfect for kids but it also worked for me.

I did the practice activities in the book and then did a more deliberate attempt when doing my Learning in Depth study of coral over the summer. It was one of the most affecting and memorable activities in and incredible 6-week course.

The Secret History of Christmas by Bill Bryson

A delightful, short little book with dozens of fascinating facts. Bryson is wonderful at making you want to look up why things happened the way they do.

Please don't try the exploding pies.

Potential spoilers below:

1: Dark Forest - The whole idea of the Sophons is genius in that they allow communication without physical interaction. The fact that they can rule out transformative technological leaps is what allows the story to work at long time scales. I do miss some of the characters from the previous book when time jumps forward. What about Wei Cheng?

Liu's ideas about how society advances and how it doesn't are fascinating. He seems to have a theory of history in the concept of the Ravine and second renaissance, but it isn't fully developed. I wish there was a bit more there.

I'm a little confused about some of the motivations, particularly why the ETO suddenly stopped being relevant - and if they did, what was Keiko Yamasuki's purpose in revealing that her husband was a defeatist? Wouldn't that help the Trisolarans? For that matter, why would any of the wallbreakers confront their targets, given their ideas would have likely failed? I loved the final gambit although I'm not convinced the it would've worked. The titular revelation is pure genius.

2: Reincarnation Blues - I found the humor a little jarring at points when the story should have been more poignant - I get that it's the style. The reincarnation aspect was frustrating as I was usually more invested in the immediate lives than the meta-story.

Comments

Post a Comment