Social Interaction 2: Examples from D&D, Naturalistic Interaction Mechanics, Ability Checks & Reaction Rolls

The previous post about social interaction explored the different areas that social rules should cover. A relatively complete system should help resolve social situations when there is conflict and uncertainty, specifically:

persuading others and resisting attempts at persuasion

lying, recognizing falsehoods (related: seeking secret information, hiding information)

maintaining relationships

This article will look at different social mechanics in published games and see how (or whether) they represent these concepts. We will also look at how players can affect outcomes and what GMs are directed to consider when adjudicating interactions.

Social Interaction Rules in D&D

We will start with the big one, looking a social mechanics from the current edition, D&D 5E, and then look at variations from earlier iterations of the game.

On page 185 in the 5th Edition Player's Handbook under social interaction the section divides interaction into roleplaying and ability checks. Under the heading Roleplaying:

'Roleplaying is, literally, the act of playing out a role. In this case, it's you as a player determining how your character thinks, acts and talks.'

I think this an okay definition but the fact that it is located as a subheading under the topic Social Interaction only helps to perpetuate the confusion between roleplaying and interacting/conversing. Roleplaying happens at every point in the game when players are determining what their character does, including combat, exploration and decision-making, not only social encounters.

The PHB goes on to distinguish between descriptive and active roleplaying. Descriptive roleplaying is when a player describes what their character does and says by narrating their actions. Active roleplaying is when 'you speak with your character's voice, like an actor taking on a role.' Players are encouraged to mix and match either of these styles.

Ability checks in D&D 5E consist of rolling a d20 against a GM-determined target number. This roll is modified by Charisma, an all-purpose social stat, and proficiency in social skills: deception, intimidation and persuasion. Insight checks based on the wisdom attribute can be rolled when a character needs to glean extra information or ascertain truths.

Ability checks thus cover areas like lying, identifying lies and persuasion with specific skills. Players do not have specific skills to resist persuasion probably because D&D typically omits mechanics that would abrogate player control over their character's actions (with the exception of certain magical effects). The illimitability of player agency is common but not pervasive among ttrpgs (as we will see with other games).

As far as adjudicating social interaction, the 5E Dungeon Master's Guide (p.244) lays out the structure of a social encounter:

1. Determine attitude

2. Roleplay

3. Charisma Check

First, the DM determines the attitude of the NPCs toward the player's characters. NPCs could be friendly, indifferent or hostile, each attitude associated with a different range of target numbers and possible requests. It's tougher to borrow a cup of sugar from your spiteful, antagonistic neighbor than borrow a car from your lifelong best friend.

Next, the players and NPCs 'roleplay' the conversation using naturalistic interaction mechanics. The GM determines player intent and decides whether the NPC will respond favorably to players' purpose. The conversation presents an opportunity for players to change an NPC's attitude; players can, after suitable conversation, make an insight check to determine an NPCs characteristics as described by their flaws, bonds or ideals (failed checks may reveal false insights). They can then appeal to a characteristic (e.g. loyalty, patriotism, greed) to improve an NPCs attitude.

When the outcome is uncertain GMs can call for a charisma check to determine the outcome of an interaction. Like most systems, contextual factors may modify rolls and multiple checks can be strung together to create more complex social challenges.

Edition Wars

Previous editions of D&D that use the unified resolution mechanic (d20 + character modifiers vs a target number): 4th Edition, 3rd, 3.5 all follow a basically similar structure. Some skills are different (e.g. diplomacy instead of persuasion) but main focus tends to be on tactical combat and there is less(!) attention to resolving social interaction.

In earlier editions of D&D stretching back to the beginning, most social encounters used were resolved using naturalistic interaction. In AD&D extensive tables of personality characteristics are provided for generating NPCs. Gary Gygax, in the AD&D Dungeon Master's Guide (p.103) gives examples of the GM taking on the role of NPCs "with no great difficulty simply by calling upon observation of basic human nature and combining it with the particular game circumstances applicable."

In these games when GMs wanted to model uncertainty they tended to invoke bespoke rules. A couple of the most common were probability rolls and roll-under ability checks.

Probability rolls (my term) are an all-purpose mechanic using the dice as a randomizer. The GM simply thinks of the likelihood of a given outcome and rolls the dice to see what happens. Situational factors and player input can be factored into the likelihood of success.

This improvisational method is useful because it can cover any situation and can be rolled openly or in secret. If you've run games for any length of time you've probably used it. One drawback is that these rolls are rather opaque and subjective, thus it can be harder for players to make informed choices to affect outcomes.

Example probability roll: Players want to bribe Harold the Guard to 'forget' to lock the back gate. The GM decides that given Harold's dislike for his employer there is a base 10% chance this will work. He adds 5% for the player's good charisma score and another 10% for the bribe. The GM tells players they have a 25% chance and rolls a d4.

This has the advantage that a GM can make the roll in a second. The downside is that because the rules are not written down, players don't know what is affecting their chances of success. Even if the GM announces the modifiers, there is no guarantee that in the next social encounter the probability will be calculated in the same way. Probability rolls are a very good tool to resolve spontaneous situations but they are not an ideal player-facing mechanic for common circumstances.

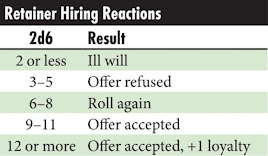

One last mechanic has been around since the earliest editions of D&D: the reaction roll. When encountering monsters or NPCs the GM rolls dice 2d6 and adds a Charisma modifier to determine their attitude toward the players. The GM can compare the results with a table like these from Old School Essentials (a B/X D&D rules clone):

For every action there is an equal but apposite reaction roll: On the Non-Player Character

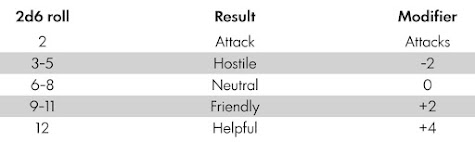

Courtney Campbell's On The Non-Player Character is a fascinating take on social interaction rules, not only for the mechanics but also for the rationale. It is built upon a framework of reaction rolls. Players make an initial 2d6 roll on encountering an NPC that sets the reaction (base attitude) toward the characters and the number of social actions possible before the NPC ends the interaction. Reaction modifies all social actions and can be changed through various means:

Players then may engage in social encounters using a dozen or more bespoke tables for different types of social actions. Some actions correspond to character goals (negotiate, demand, bluff, hire, gamble, sneak attack). Each action has its own modifiers and results:

For example, the demand action requires the player to roll 2d6 ≥ the target's morale score (a number from 2 to 12) and this roll is modified by the player's charisma and the difficulty of the demand. On a success, the target accedes to the demand. On a failure, the player's reaction becomes hostile and future social rolls are penalized by -1.

A number of the other social actions are aimed at shifting NPC opinions. Some of these actions could be characterized as rhetorical approaches whereas others fall into the category of relationship management. Grovel, honor (praise), joke, or [offering a] drink all affect short-term relationships by changing NPC reactions or adding a modifier to social rolls. Each of these mechanical effects end at the end of the encounter (though NPCs do tend to have memories). Over time, players can build a lasting connection with NPCs as represented by a bond score. Social actions like [giving a] gift, seduce, relax (spending time together) can all increase the bond when properly applied. Some actions like threaten aim to achieve powerful immediate results at the cost of reducing long-term player/NPC bond.

There is even more to On the Non-Player Character: An action for converting people to other religions and beliefs, a system for generating NPCs and a detailed explanation of how to construct complex social problems using beliefs as 'locks' and 'keys'. If it all sounds a bit overwhelming it definitely can be. The idea is to create a system that elevates social interaction to the level of combat in terms of rules support.

Campbell provides a basic, generic social action for times when no other social action fits or GMs can't be bothered to look up the rules. Basically roll 2d6 modified by charisma and current reaction: 2 failure, 3-5 rejection, 6-8 undecided (counter-offer), 9-11 success, 12 total success.

Fluff vs Crunch: Naturalistic vs "Rules-First" Interaction

So when should GMs use more conversational, naturalistic interaction rules and when should they lean into more abstracted systems? As we have seen with D&D social interaction rules, the default is to use naturalistic interaction for social encounters and then to roll dice when the GM can't be certain how the NPC would respond. The 5E version of this is 'roleplay' followed by an ability check to determine the outcome of the scene. One way of describing this model is fiction-first mechanics, in which players engage with the world diegetically (in-world) before the game mechanics are engaged. Naturalistic, fiction-first approaches to social interaction have the benefit that they mirror players' real-world experiences of conversation, aiding immersion.

The opposite, "rules-first" method is one where players can appeal directly to the rules to establish character action. A classic example of this is when players enter a room and the GM's description piques their suspicion that something is hidden: The players announce their desire to make a perception check without specifying any in-fiction action taken by the characters. Rules-first systems are rather out of fashion in RPG circles at the moment; they face criticism for undermining roleplaying by turning the game's fiction into something more like a board game or worse yet, an optimization problem.

The reaction rolls and other rules described in On the Non-Player Character explicitly enable (but do not require) a rules-first approach. Players can enact social actions by specifically calling out the mechanics if they so choose. In order to understand why you would want to allow or even encourage this, it helps to take a look at Campbell's rationale for the book. He sees his system as a codification and expansion of existing social rules designed to be compatible with D&D.

The idea is that social interaction should be based on player skill, not inherent player social ability nor solely based on skills written on character sheets. We all know people with the gift of the gab and the idea here is that they shouldn't necessarily be better at RPG social interaction than the most physically athletic player at the table should be better at RPG combat. This a matter of accessibility; Nobody needs to demonstrate their swordsmanship in order to make an attack roll. To achieve these goals On the Non-Player Character needs to make the rules accessible at both the conversational level and a more abstracted level. Thus, a player can go "fiction-first" and use their real-world conversational skill to invoke beneficial modifiers but they can alternatively engage with the rules and describe their intention so that they can resolve the outcome mechanically.

Having specific, procedural rules that can be approached "rules first" also helps players by providing transparency. Players can engage very deeply with a system when they can see the rules and make plans based on predictable outcomes. If, on the other hand, outcomes seem random or biased then they are disincentivised from engaging. Another benefit is that explicit recourse to the rules prevents games of social encounter "Mother, May I?" in which players must constantly ask the GM which approaches might be valid or guess the NPC's password in order to proceed.

Naturalistic interaction and rules-first social interaction systems are not always in opposition. As described both in D&D and the supplement On the Non-Player Character, the rules can support both approaches and allow players to toggle between them. Rules-first and fiction-first only describe the order in which the rules and in-game diegetic actions are invoked. For immersion, it is perhaps even more important that the resolution mechanics support the in-game fiction. It is possible to have naturalistic systems that rely on highly unintuitive, disassociated resolution mechanics. By the same token there can be highly complex, rules-first systems that closely model real-world situations, creating a sense of congruence between game world and mechanics. A good GM will act as translator for players, asking them to clarify both their intents and the in-fiction methods they plan to use for attaining these goals, helping to fill in any blanks that arise. There should be at least as much room for good will and negotiation among the players and GM over how the game is played as there is among the characters they portray.

It is possible to build abstracted rules structures on top of naturalistic interaction rules and thus develop systems for social interaction that would be difficult with only one type or the other. I hope to explore some of these structures including relationship mechanics, reputation, and tracking NPC beliefs in future articles. If you were hoping to read about mechanics from a different game you may be in luck as I plan to draw on a whole new set of systems, too.

_(14582544550).jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment