How Do You Learn?

Have you ever had the experience of thinking back to a fondly-remembered book or film or personal experience only to come away with the realization that you don’t remember anything about it? It was a great story: What was that character’s name?

I find these types of lapses disturbing because one of the great feelings when reading is the feeling of accreting knowledge, of gradually improving my understanding. I hate the sneaking suspicion that I’ll forget everything in a few months. I’ve made some progress but forgetting is always going to be an issue.

I’m writing down my current learning habits so that I can hopefully continue to improve on them in the future. I’m not sure how entertaining this will be to read, so apologies if it’s a bore.

New content and discovery:

I tend to get a lot of information from blog posts. I aggregate this mostly via Blogger and Substack. I like that the blogs I choose to follow are highly intentional sources and the quality of information they provide tends to be deeper than other types of social media. Blogs usually also provide good recommendations for other sources, probably because blog writers tend to be passionate about their topics in ways other people online generally aren’t. This blog could be described as an attempt to connect to the Great Conversation, Mortimer Adler’s term for the historical current of intellectual and aesthetic discourse.1

I avoid most forms of social media because I find they tend to prey on my emotions and waste my time. I’m not sure whether this due to the constraints of the medium or whether they simply tend to foster subcultures I don’t connect with. Reddit and Youtube are two exceptions, which I tend find useful for entertainment and content discovery, plus keeping abreast of people I follow.

A lot of brilliant people use twitter but I only ever go there for links. The interface is unituitive for me and I can’t stand trolling through dross to find the content.

I don’t read much traditional news but when I do I tend to use the BBC app or simply scroll through the Google feed on my phone. I tend to lean away from current events toward information with less of a shelf life, but this does put me out of touch with the kinds of information most people prioritize.

Study and Practice:

The sources I use for delving deeper into topics of interest are books, supplemented by internet search, wikipedia and AI sources. I maintain an ever-growing list of books to read in various subject areas and pull off the pile more-or-less according to fancy. As I read I take notes, usually in a google doc or occasionally in Kindle. I like digital notes because they are searchable and can be synchronized across devices. I have heard hand-written notes are better for memorization but I tend never to go back and review them.

A sidenote on audio: Sometimes I listen to audiobooks, particularly when exercising but have found audio is a terrible method for taking in new information. Even when listening to fiction for pleasure I often end up needing to reread chapters. Podcasts are another popular category I don’t use a lot because they tend to be less informationally dense than written sources and I don’t retain them very well.

Basically visual input > auditory. I think this is because listening forces me to attend at a certain rate whereas when reading I can return important sections over and over.

Ideally I would read a few books in the same subject area at a time, to get different viewpoints and benefit from clusters of knowledge, but don’t pull this off as much as I’d like.

Because of my lack of focus in a single area I’m often stuck in the early stages of learning a new topic where subject specific vocabulary and concepts are major stumbling blocks. I often resort to wikipedia and GPT4 in these types of situations. I feel like I underuse AI compared to more prolific learners, particularly by not uploading whole documents or using preconfigured task-specific instructions.2

SRS and Retention:

I started using Anki a couple of years ago and it has helped me to better enjoy informational reading because I am more confident that I will remember the important parts of the book.

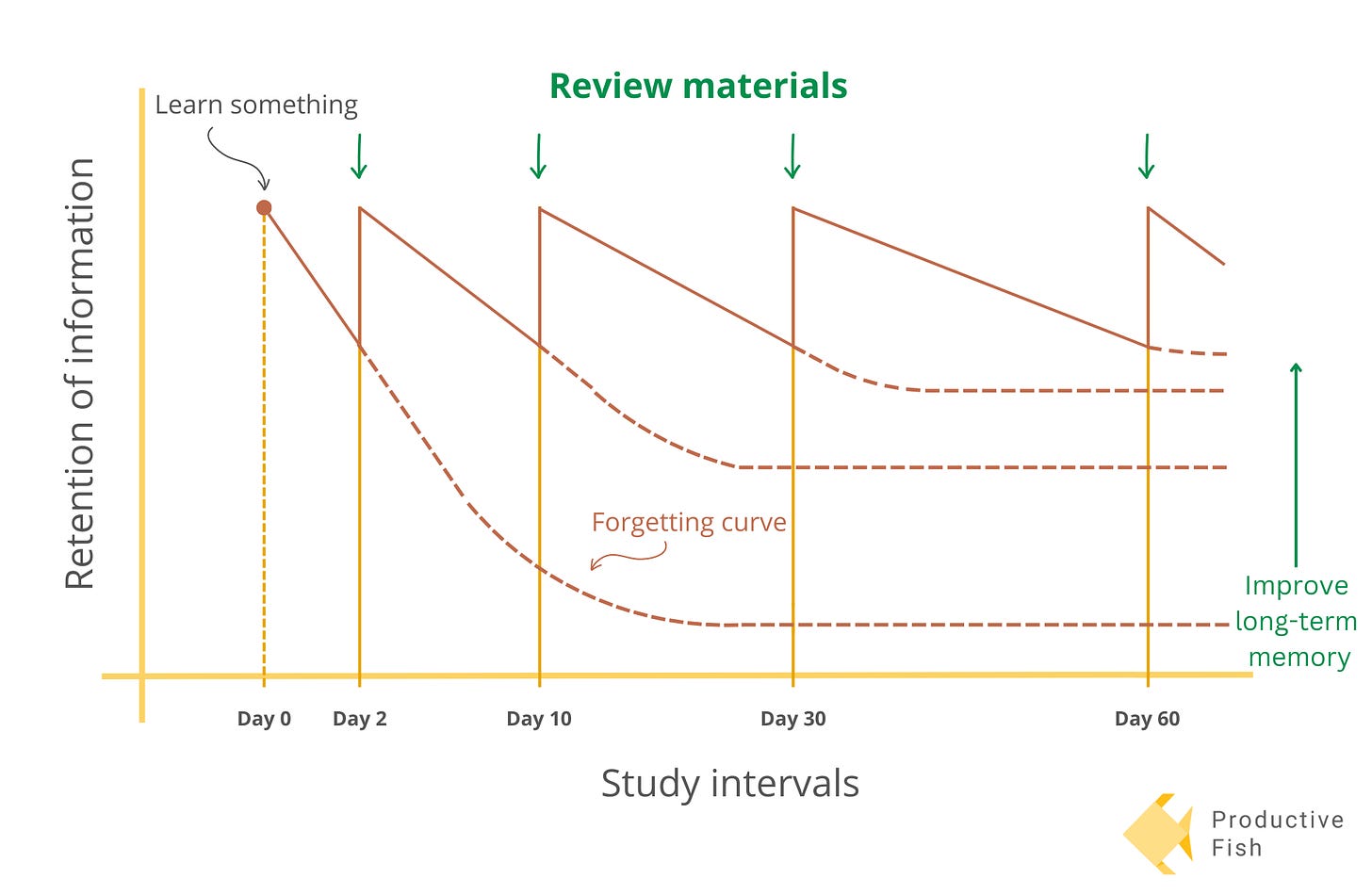

Anki is free spaced-repetition-software (SRS) that allows you to create your own flashcards. Each card appears for review at increasing interval. Seven or so rehearsals are required before the duration gets over a year. I use it daily for all sort of things: key ideas from my book notes, definitions, conceptual information, personal memories, etc. I find that the variety helps keep it from being boring. Most days I create several flashcards and I tend to spend about 20 minutes reviewing daily.

Does it work? It works! There are a couple of downsides that aren’t immediately obvious. First, SRS helps you to retrieve information, but it doesn’t necessarily make that retrieval immediate or effortless. That means that if you really need to remember something, usually you can. Another problem arises when you don’t use the information regularly: gradually the context and salience tends to erode. In an ideal world, any information you memorize would pop unbidden into your head whenever it became relevant. I find that this isn’t the case. SRS does not magically enhance my creativity or allow me to eidetically recall information at the speed of conversation. Limitations aside, however, I do notice improved recall (probably through practice) and far better retention of my reading than before I began using Anki.

Great, I’ve solved learning… False!

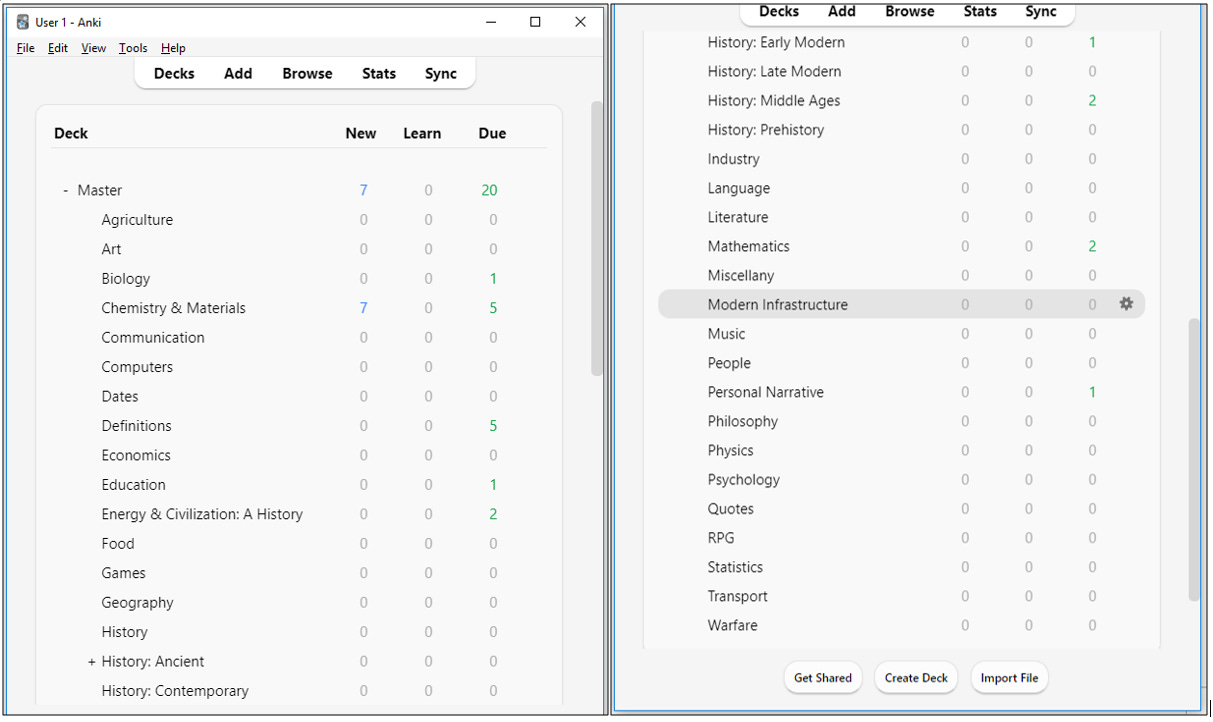

You may wonder what, specifically I’m studying. Most Anki users are either med students or language learners. Here’s a screenshot of my Anki decks:

You can see from the screenshots that the variety of topics I tend to cover pretty much precludes mastery of any one of them. This brings me to the downsides to my learning choices:

I lack opportunities to purposefully practice a lot of the information I take in. The learning is often unconnected to a specific goal other than personal interest.3 This makes it harder to develop the sorts of relevance and salience necessary to use the information for productive work. As a result, I tend to accumulate masses of relatively trivial facts. To be clear, the facts are not inherently trivial but they are trivialized because they lack connections to each other and a context for use.

One major area exception is education: I try to integrate new educational ideas into my teaching practice wherever possible but this is a large bottleneck. I run across too many good ideas to implement even a significant fraction of them. For other interests (like game design) I can also put my learning to use but at a much slower rate than in my day job.

Another critique of my process is that it is very slow. Reading deliberately, taking notes and loading information onto spaced-repetition flashcards takes a lot of time. Would I be better off going through reams of related books and developing expertise through a sort of osmosis? I’m not certain. My intuition is that it would work better for initial impressions and less well for developing deep understanding.

Are there any other shortcuts that could speed up the process?

I do think there are several: First, culturally-mediated ideas seem to be easier to disseminate and retain. Groups that prioritize certain types of discourse are good at developing tools to transmit that information: jargon, memes, increased salience, common practices, etc. So join a club.4

Another trick is to develop emotional connection to the information. One way to do this is to argue about discuss it with someone. It is difficult to find people with the time necessary to learn in parallel with you, but if you can - it is the ideal. Finding a mentor is another high-upside possibility.

Putting information to practical use helps to internalize and deepen learning as well. It is easy to learn something you can practice regularly. If I could change anything now I think it would be developing more active, goal-based learning projects even if that means spending a bit less time on research.

I have always been comparatively good at finding emotional resonance with relatively dry, disconnected facts. I guess my perhaps vain hope is that one day all of these seemingly unconnected facts continue to accrete until they DO connect into some sort of grand tapestry of truth.

I think we can extend this concept to the entirety of human cultural discourse, like Kieran Egan does, rather than confining it to Western thought.

Oddly enough, I haven’t used any LLMs directly for writing. Perhaps it would improve my work but it feels alienating to see my thoughts filtered through another.

Not knocking learning for fun.

Michael Strong writes about creative effective educational subcultures and I think his ideas are great.

Comments

Post a Comment